Art is much more than aesthetics and personal expression. Across centuries and civilizations, art has served as a primary method of documenting cultural realities—what people believe, how they live, the values they hold, and how they interpret their world. From cave paintings in prehistoric times to contemporary multimedia installations, art captures the lived experiences of communities in ways that archives, statistics, and written histories cannot.

In this article, we explore the multiple dimensions of art as cultural documentation. We examine how artworks serve as historical records, enable identity formation, preserve memory, and offer critiques of power and society. We also include key concepts, examples, and practical SEO keywords to support online publishing.

Defining Cultural Documentation Through Art

What is Cultural Documentation?

Cultural documentation refers to the recording, preservation, or representation of the beliefs, rituals, norms, material culture, and practices of a group. While anthropology and history use texts, interviews, and artifacts, art adds a deeply experiential dimension—imbuing documented culture with emotion, metaphor, and visual power.

Artworks can function as:

- Primary records of events or traditions.

- Symbolic narratives capturing belief systems and worldviews.

- Reflections of social structures—power, gender, class, and race.

- Tools for cultural survival and memory transmission.

How Art Differs from Other Forms of Documentation

While written documentation offers explicit detail, art provides interpretive insight. For example:

- A photograph captures a moment; a painting can convey emotional impact.

- A mural can narrate a community’s struggle better than descriptive prose.

- Performance art can embody rituals or resistance in ways that words alone cannot.

Historical Perspectives on Art as Documentation

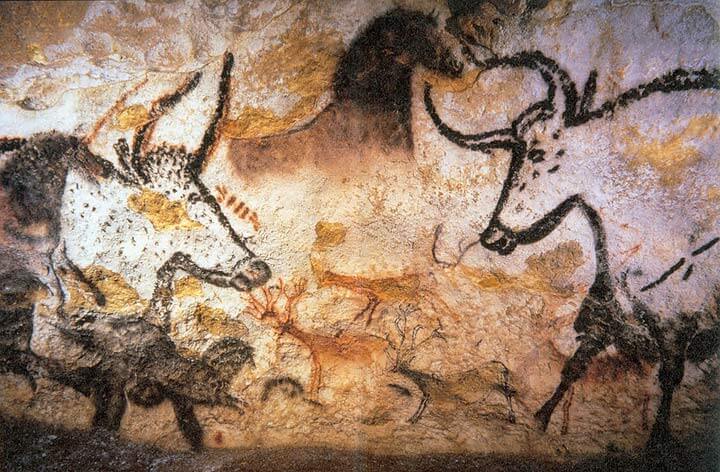

Prehistoric Art: The Earliest Records

The oldest surviving artworks—cave paintings, hand stencils, and engravings—are more than creative expression; they are records of human existence. These visual documents show:

- Daily activities (hunting scenes)

- Religious or spiritual beliefs (symbolic shapes)

- Interactions between species and the environment

Examples like the Lascaux Caves in France and Altamira in Spain reveal the complexity of early human cognition and cultural life.

Ancient Civilizations: Art as State Documentation

In ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China, art documented politics, religion, and daily life. Reliefs, temple paintings, and sculptures served as:

- Royal propaganda (pharaohs and emperors)

- Mythological narratives

- Funerary practices that communicated beliefs about life and death

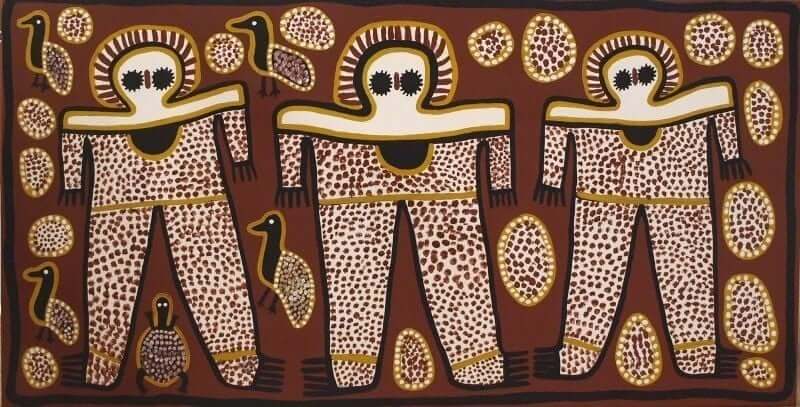

Indigenous Art and Cultural Continuity

Indigenous Art as Living Documentation

For many indigenous cultures, art is not a static record but a living archive, continuously renewed and transmitted through generations. Examples include:

- Totem poles and carvings

- Body painting and ritual masks

- Weaving patterns and beadwork

These artistic practices encode cultural knowledge—stories of origin, laws, cosmology, and kinship.

Case Study: Aboriginal Rock Art (Australia)

Aboriginal rock paintings in Australia represent one of the longest continuous artistic traditions on Earth, with some works dating back tens of thousands of years. These images:

- Record ancestral stories (Dreaming)

- Map seasonal movements and resource sites

- Affirm cultural identity across time

These are not relics but ongoing visual languages.

Religious Art as Cultural Narrative

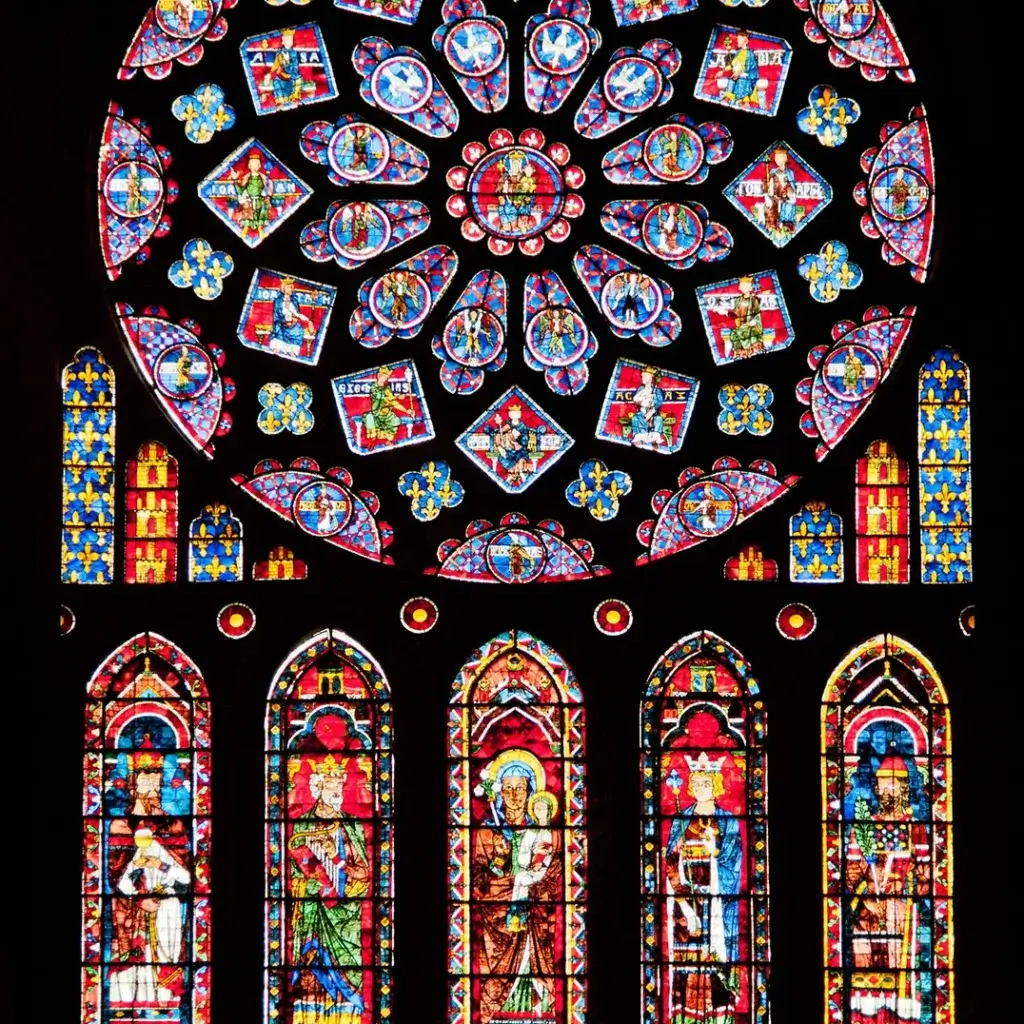

Sacred Spaces and Visual Theology

Religious art—icons, frescoes, stained glass, temple decoration—serves as visual theology. It teaches beliefs, instills moral values, and shapes community cohesion.

Examples:

- Byzantine icons transmitting biblical stories

- Gothic cathedral windows as illuminated scripture

- Hindu temple carvings illustrating Puranic mythology

Art in religious contexts records evolving doctrines, devotional practices, and community identity.

The Function of Ritual Art

Ritual objects—masks, altars, ceremonial garments—function as cultural documents that encode cosmology and cultural order. Their forms and materials signify hierarchy, taboo, and sacredness.

Art in Times of Conflict

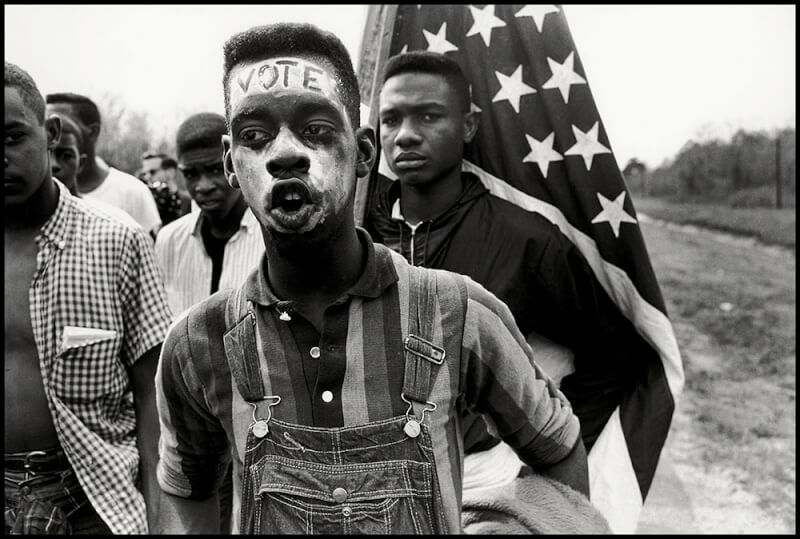

Art as Witness to War and Violence

Art during conflict plays both documentary and political roles. It preserves truth, challenges power, and archives trauma.

Examples:

- Goya’s The Disasters of War

- Picasso’s Guernica

- Photographs from the Civil Rights Movement

These works do not merely represent events—they interrogate violence, human suffering, and the moral responsibilities of societies.

Art as Resistance and Memory

In many oppressed and colonized communities, art becomes a tool of resistance. It reclaims narratives, asserts presence, and counters erasure.

Contemporary Art and Social Documentation

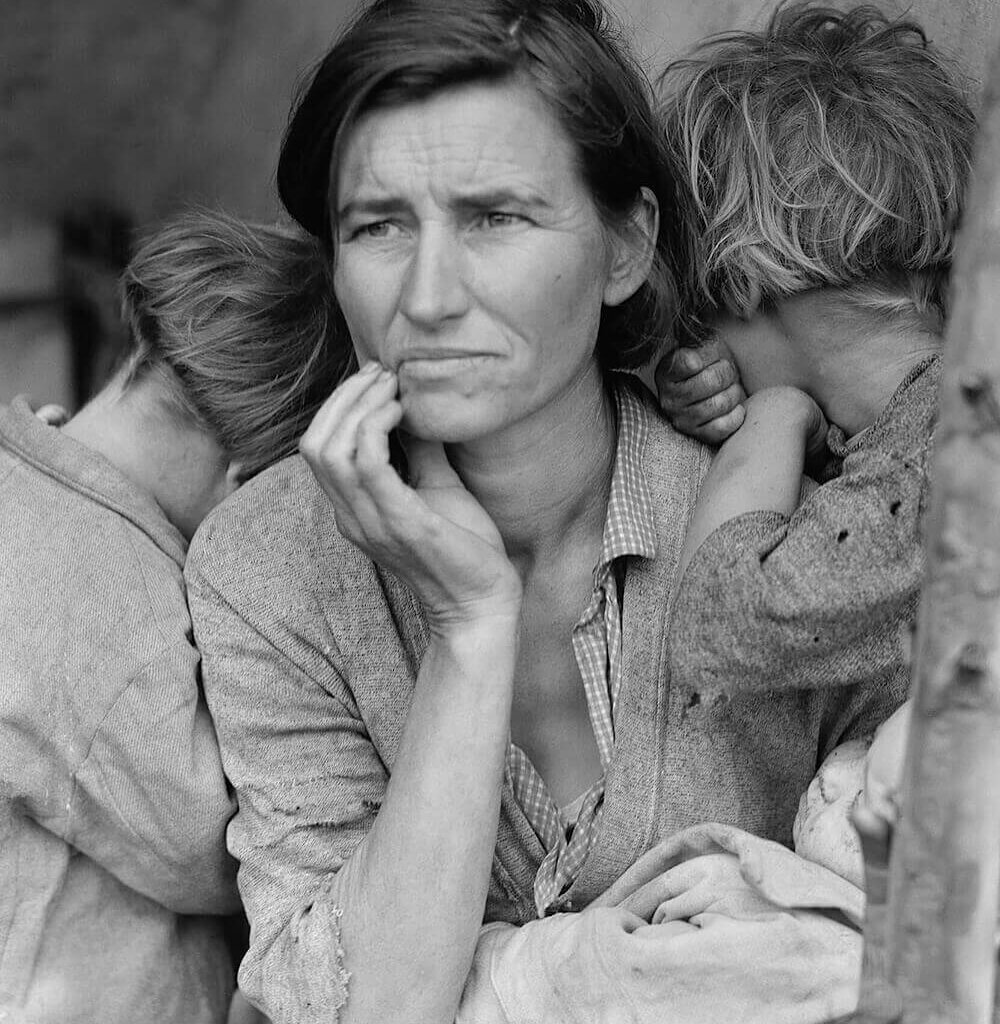

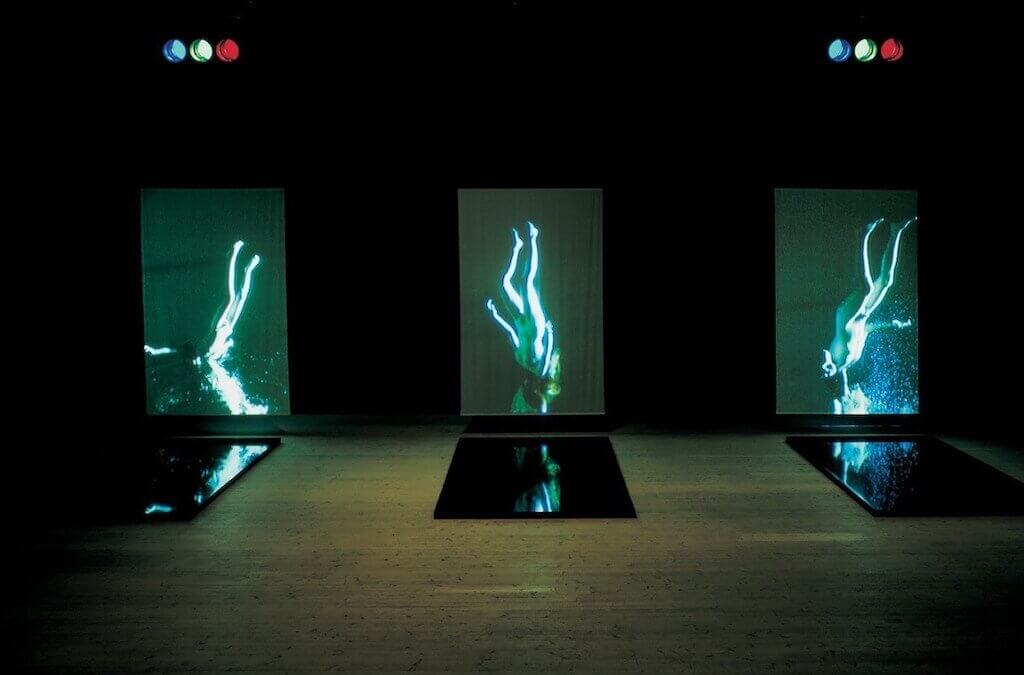

Documentary Photography and Video Art

Photography and video art have become central to how we document contemporary life. They offer:

- Immediate visual records

- Multimodal storytelling

- Platforms for underrepresented voices

Documentary art forms capture daily life, social struggles, environmental change, and more.

Performance Art and Public Memory

Performance art often takes place in public spaces, engaging communities directly. It can mark events, protest injustice, or celebrate identity.

These ephemeral works, though temporally limited, are documented through photography, film, and audience memory, contributing to collective cultural records.

Digital Art and New Media as Cultural Record

The Digital Turn in Cultural Documentation

The rise of digital art—virtual reality, NFTs, interactive installations—has expanded how cultures record and access artistic documentation. Digital platforms democratize creation and circulation.

Digital art:

- Preserves intangible cultural practices

- Enables global access to local stories

- Challenges traditional boundaries of museums and archives

Challenges and Opportunities

While digital art expands reach, it also raises concerns:

- Preservation of digital media over time

- Accessibility in areas with limited technology

- Authenticity and replication (e.g., deepfakes)

Addressing these issues is part of the evolving landscape of cultural documentation.

Museums, Archives, and Art Preservation

Museums as Custodians of Cultural Memory

Museums curate collections that tell stories about cultures, epochs, and worldviews. Exhibitions organize artifacts and artworks in ways that:

- Educate publics

- Foster cultural appreciation

- Drive historical interpretation

However, the museum’s role is also contested—especially regarding repatriation, decolonization, and biases in representation.

Archives and Art Conservation

Beyond displaying works, institutions preserve them. Conservation science protects fragile media—paint, film, textiles, digital files—ensuring that future generations can access cultural records.

Case Studies in Art as Cultural Documentation

Case Study 1: The Mexican Mural Movement

In the early 20th century, Mexican muralists (Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros) transformed public buildings into massive visual histories. These murals:

- Documented indigenous heritage

- Celebrated revolutionary ideals

- Claimed public space for collective memory

Their works remain living cultural documents reflecting national identity.

Case Study 2: The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance (1920s–1930s) was a cultural flowering in African American art, literature, and music. Artists like Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage documented:

- Black life and history

- Aspirations for equality

- Cultural resilience in adversity

Their art helped define modern cultural narratives in the United States.

Art Education and Cultural Literacy

Why Art Education Matters

Teaching art is not merely about technique—it builds cultural literacy. Students learn:

- How to read visual narratives

- Critical thinking about context and bias

- Respect for cultural diversity

This expands appreciation of art as a documentary source of knowledge.

Integrating Cultural Documentation into Curriculum

Schools and universities can integrate art history with anthropology, sociology, and media studies to foster deeper cultural understanding.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Art as Cultural Documentation

Art remains one of humanity’s most powerful tools for documenting culture. It transcends language, survives epochs, and connects people across time and space. Whether carved on cave walls, painted on temple ceilings, or coded as digital experiences, art records what it means to be human.

When we engage with artworks as cultural documents, we unlock not only historical knowledge but also empathy, shared memory, and collective identity.