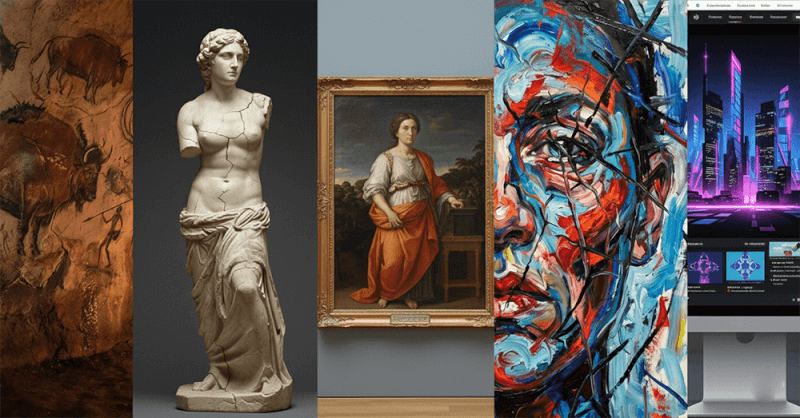

Art is one of humanity’s most enduring and adaptive forms of expression. From the earliest marks scratched on stone to the abstract and conceptual works of the modern era, art has continuously evolved to reflect cultural shifts, technological advancements, and changing philosophical understandings of the human experience. This article traces major art styles across historical epochs, examining how social context, materials, and ideas shaped artistic practices from prehistory to the contemporary moment.

Prehistoric Art

Art has its earliest roots in the Paleolithic period, roughly 40,000 to 10,000 BCE, when humans first began to create enduring visual expressions. Prehistoric art appears across multiple continents, with cave paintings, portable sculptures, and carved objects offering insight into early human cognition and ritual practice.

Prominent examples include the Lascaux Cave paintings in France and the Altamira Cave art in Spain. These works feature animals such as horses, bison, and deer, rendered with remarkable observational skill and dynamic composition. Scholars interpret these creations as part of hunting rituals, spiritual belief systems, or early mythic frameworks.

Ancient Civilizations

As human societies developed agriculture and urban life, art became more structured and symbolic. Ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China produced highly sophisticated visual cultures that reflected religious functions, political power, and cosmological orders.

- Egyptian Art: Characterized by its adherence to strict conventions, stylized figures, and funerary contexts. Wall reliefs and tomb paintings depicted gods, pharaohs, and the journey to the afterlife with symbolic precision.

- Mesopotamian Art: Ziggurats, cylinder seals, and relief carvings from Sumer, Akkad, and Babylon emphasized narrative scenes and divine kingship.

- Indus Valley Art: Sculpture and seal engravings from Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro exhibit abstracted animals and ritual motifs.

- Ancient Chinese Art: From oracle bone inscriptions to Bronze Age ritual vessels, Chinese art combined functional objects with ceremonial meaning.

Classical Antiquity (Greece and Rome)

The cultural achievements of ancient Greece and Rome represent a pinnacle in the development of proportion, perspective, and realism. Greek sculpture pursued an idealized human form, as seen in works such as the Doryphoros of Polykleitos. Architecture followed mathematical ratios, culminating in structures like the Parthenon.

Roman art, while heavily influenced by Greek precedents, innovated in portraiture, fresco painting, and engineering solutions such as the arch and concrete.

Medieval Art (Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic)

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, European art entered a period of transformation characterized by religious centrality and symbolic representation.

- Byzantine Art (c. 500–1453 CE): Mosaics, icons, and richly ornamented liturgical objects emphasized spiritual transcendence.

- Romanesque Art (c. 1000–1150 CE): Architectural forms such as thick walls, rounded arches, and monumental sculpture were adapted to cathedral design.

- Gothic Art (12th–15th centuries): Cathedrals with flying buttresses, luminous stained glass, and intricate stone carving signaled new advances in engineering and devotional art.

Renaissance and Mannerism

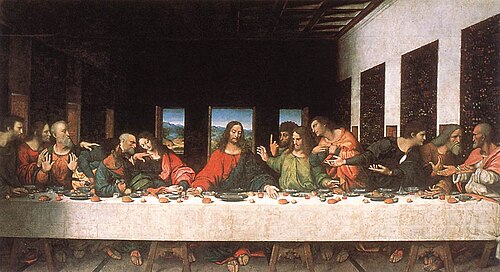

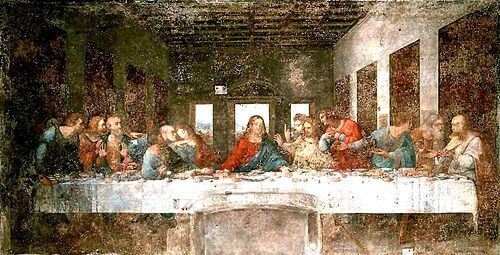

The Renaissance (c. 14th–17th century) marked a rebirth of interest in classical learning, humanism, and empirical observation. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael pursued anatomical precision, perspective, and atmospheric rendering. The result was an explosion of painting, sculpture, and architectural innovation, particularly in Italy.

Following the High Renaissance, Mannerism emerged, stretching proportions and introducing ambiguous spatial compositions to evoke emotion and elegance.

Baroque and Rococo

The Baroque period (c. 1600–1750) is defined by dramatic movement, rich coloration, and intense light-dark contrasts known as chiaroscuro. Artists such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt created emotionally charged works that engaged viewers physically and spiritually.

Rococo, a later 18th-century development, favored ornamental complexity, pastel palettes, and playful subject matter, exemplified by artists like François Boucher and Jean-Antoine Watteau.

Neoclassicism and Romanticism

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw contrasting responses to social upheavals such as the American and French Revolutions.

Neoclassicism revived classical themes and moral clarity with artists like Jacques-Louis David, emphasizing order and civic virtue.

By contrast, Romanticism, embodied by Eugène Delacroix and Caspar David Friedrich, prioritized individual emotion, nature’s sublimity, and dramatic narrative.

Realism and the Advent of Modernity

Mid-19th century Realists such as Gustave Courbet rejected idealized depictions, instead presenting gritty, everyday life with unvarnished honesty. Realism aligned with broader cultural shifts, including industrialization, the rise of the middle class, and expanding literacy.

At the same time, photography began to influence composition and representation, ultimately altering the role of painting itself.

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

The late 19th century saw seismic change as artists broke from academic conventions. Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro captured fleeting light and sensation using loose brushstrokes and vibrant palettes. Parisian life, landscapes, and moments of leisure became valid and celebrated subjects.

Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Georges Seurat expanded expressive possibilities through structural experimentation, color theories, and pointillist techniques.

Early 20th-Century Movements

The early 20th century ushered in radical approaches that dismantled traditional representational norms.

- Fauvism: Led by Henri Matisse, characterized by wild, arbitrary color.

- Cubism: Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the fragmented form and multiple perspectives.

- Futurism: An Italian avant-garde emphasizing speed, technology, and dynamic motion.

These movements collectively challenged fixed viewpoints and set the stage for greater abstraction.

Modernism and the Avant-Garde

Between World Wars I and II, art became increasingly experimental. Movements such as Dada and Surrealism questioned the very definition of art.

- Dada: Anti-art provocations that criticized rationality and bourgeois culture.

- Surrealism: Linked to Freudian psychology, artists like Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst created dreamlike imagery that destabilized logic.

Modernism also saw abstract tendencies in works by Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, who divorced art from recognizable objects.

Abstract Expressionism and Post-War Art

After World War II, Abstract Expressionism emerged in the United States as a dominant movement. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko emphasized gesture, scale, and emotional intensity through non-representational means. Pollock’s “drip paintings” and Rothko’s fields of color exemplify art’s capacity to communicate through pure form and materiality.

This era also saw the rise of Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art, each redefining art’s relationship to culture, commerce, and idea over object.

Pop Art to Contemporary Practices

Pop Art, with figures like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, drew on mass media and consumer imagery to critique and celebrate popular culture. The blurred boundaries between high art and everyday life became a central theme of late 20th-century art.

Subsequent decades saw a proliferation of styles and approaches: performance art, installation, street art, feminist art, and global contemporary practices. Artists like Yayoi Kusama, Ai Weiwei, and Banksy engage political, ecological, and participatory dimensions in their works.

Digital and New Media Art

The 21st century has seen the rapid integration of digital technology in artistic creation and dissemination. Digital painting, 3D modeling, algorithmic art, and interactive installations have expanded artistic tools. Additionally, platforms such as social media and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) have transformed how art is experienced, collected, and valued.

Contemporary practitioners explore immersive environments, augmented reality, and AI-generated aesthetics, raising new questions about authorship and creativity.

Conclusion: Art in the 21st Century

Throughout history, art has functioned as a mirror to society’s evolving values, conflicts, and aspirations. From the earliest cave paintings to contemporary digital expressions, artistic innovation reflects humanity’s enduring impulse to make meaning of our world.

In the 21st century, art continues to diversify across media, cultures, and platforms. Globalization connects traditions while challenging established hierarchies. Technology accelerates experimentation, expanding both aesthetic possibilities and critical discourse.

As we look forward, the evolution of art remains open, shaped by networks of creators and audiences who constantly redefine what art can be.