What Is the Spiritual Dimension of Art?

At its core, the spiritual dimension of art refers to how visual expression can communicate, evoke, or facilitate experiences that transcend ordinary perception. This dimension is not restricted to religious art; it extends to any artwork that invites introspection, evokes a sense of wonder, or embodies an encounter with the numinous.

In everyday culture, art often serves decorative or entertainment purposes. However, in its most profound instances, art becomes a vehicle for meaning-making that touches the sacred: the unseen, the ineffable, and the deeply felt.

Historical Roots of Spiritual Art

Human history reveals a deep and enduring association between art and spiritual life.

Prehistoric and Indigenous Traditions

Long before formal religions, humans painted on cave walls, carved figures, and decorated sacred places. These markings often correspond with ritual activity, shamanistic practices, or cosmological beliefs.

- Cave paintings at Lascaux and Altamira contain symbols that suggest ritual significance rather than mere decoration.

- Indigenous cultures worldwide integrate art into sacred ceremonies—body painting, masks, totem poles—which embody spiritual relationships with nature and ancestors.

Ancient Civilizations

Civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, and Mesoamerica created monumental art tied to spiritual cosmologies:

- Egyptian tomb paintings and sculptures ensured continuity in the afterlife.

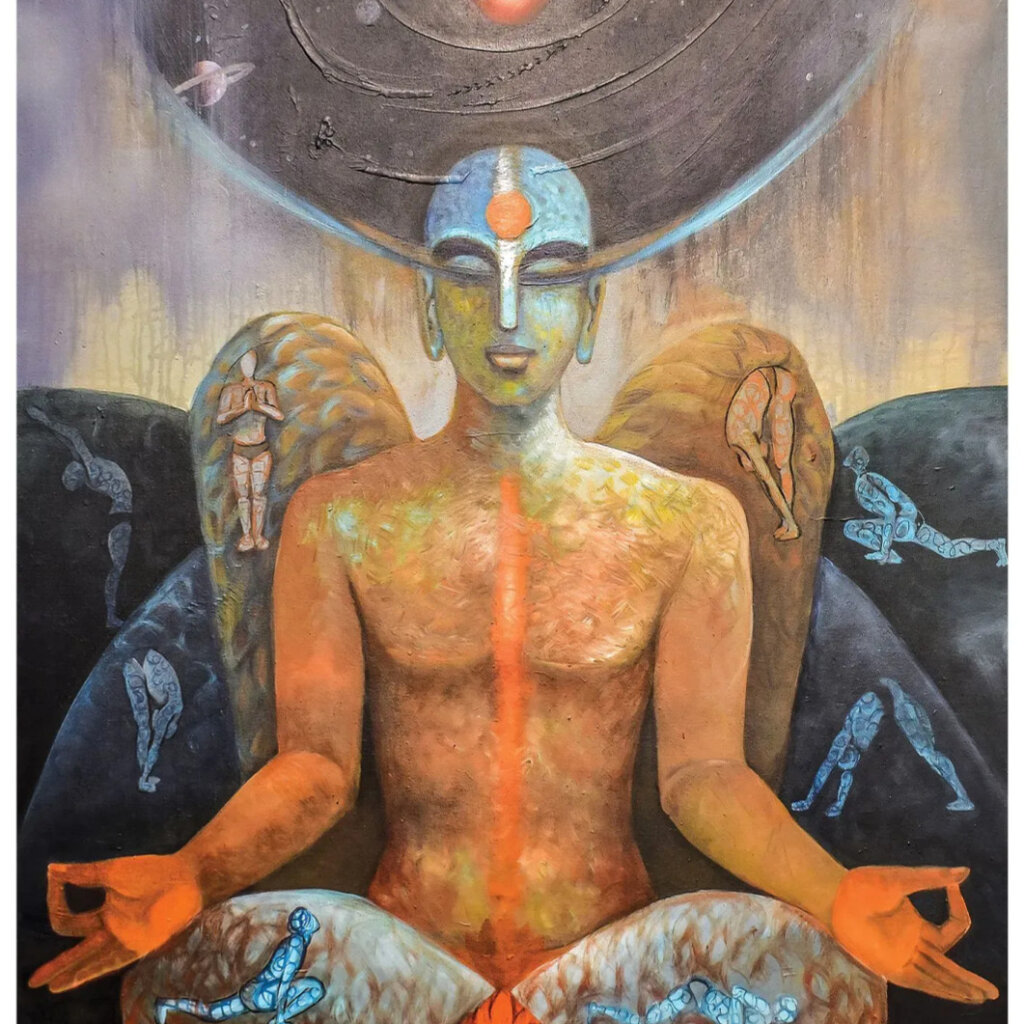

- Hindu and Buddhist temple reliefs depicted divine narratives and served as meditation aids.

- Chinese calligraphy was revered not only as an aesthetic expression but as a disciplined spiritual practice.

These traditions demonstrate that art and spirituality were not separate domains but interwoven facets of life.

Universal Themes: Sacred Symbolism and Archetypes

Across cultures and eras, certain themes recur—symbols that point to shared human questions and spiritual aspirations.

Light and Illumination

Light is a universal metaphor for truth, knowledge, and divine presence.

- Stained glass windows in Gothic cathedrals transform sunlight into colored light—symbolizing divine revelation.

- Enlightenment in Buddhism is often depicted as a radiant halo around enlightened beings.

Circle and Mandala

The circle symbolizes unity, wholeness, and cosmic order.

- Mandalas in Hinduism and Buddhism are spiritual diagrams used in meditation.

- The Celtic Cross and labyrinths in Western traditions similarly represent spiritual paths and cosmic balance.

Sacred Geometry

Many sacred traditions employ geometric forms believed to reflect divine laws:

- The Flower of Life pattern appears in diverse spiritual contexts.

- Proportions in Renaissance art were inspired by philosophical ideas about cosmic harmony.

These archetypes are not merely decorative. They function as visual languages that communicate spiritual truths beyond words.

The Artist as Mystic: Creation as Contemplation

Many artists have described the act of creation as a form of spiritual practice. For them, art is not an object but an experience—a way of being fully present.

The Creative State as Meditation

When artists enter a flow state—fully absorbed, time dissolving—they often describe the experience in terms akin to spiritual union.

- Abstract painters such as Mark Rothko conceptualized color fields as spaces for contemplation.

- Calligraphers and Zen painters see the act of brushstroke as a direct expression of mind and spirit.

Inspiration and Transcendence

Artists often speak of inspiration as something that comes through them rather than from them, suggesting a channeling of creative force beyond the self.

This resonates with mystical traditions across religions, where insight is received rather than manufactured.

Viewer Experience: Art as Meditation

The spiritual dimension of art is not only in the artist’s intention but in the viewer’s experience. Some works act as mirrors, reflecting the inner landscape of the viewer.

Thresholds of Perception

Certain artworks encourage slowing down, prompting prolonged attention and introspection.

- Minimalist art can quiet the mind.

- Repetitive patterns invite trance-like focus.

- Portraits with intense gazes can evoke emotional resonance.

Emotional and Somatic Responses

Spiritual art may evoke:

- Awe or wonder

- Peace or stillness

- Deep emotional release

These responses are not incidental but central to the work’s impact.

Art, Ritual, and Community

In many cultures, spiritual art is inseparable from collective practice.

Sacred Spaces and Communal Art

Temples, churches, mosques, and shrines are themselves works of art—designed to evoke sacred presence.

- Mosaic floors, frescoes, and icons structure communal worship.

- Ritual objects—mandalas, masks, banners—engage communities in shared symbolic acts.

Festival Art and Performance

Ceremonial arts—dance, music, masked pageantry—integrate visual and performative dimensions, uniting participants in shared transcendence.

Contemporary Expressions of Spiritual Art

Spiritual art has not disappeared with secularization; it has evolved.

Abstract and Conceptual Art

Artists in the 20th and 21st centuries have explored spirituality beyond religious iconography.

- Rothko, Kandinsky, Agnes Martin, and Brice Marden explored inner landscapes through abstraction.

- Installation and light art create immersive experiences that dissolve boundaries between viewer and work.

Digital and New Media Art

Technology enables new forms of contemplative art:

- Virtual reality environments designed for meditation and reflection.

- Projection art in sacred spaces reinterpreting ancient symbols.

Cross-Cultural and Interfaith Art

Contemporary artists blend traditions—Eastern and Western, indigenous and global—highlighting the universality of the spiritual impulse.

Challenges and Critiques

The spiritual dimension of art is not without controversy.

Secular Critiques

Some critics argue that attributing spiritual meaning to art can be subjective or escapist in a complex world facing urgent social issues.

Commercialization and Authenticity

The art market’s commodification of spiritual imagery raises questions about authenticity versus aesthetic trendiness.

Cultural Appropriation

Engagement with sacred symbols from cultures outside one’s own requires sensitivity and respect to avoid appropriation.

A responsible engagement with spiritual art acknowledges these challenges without dismissing the depth of human longing for meaning.

How to Experience Art Spiritually

For those seeking deeper engagement with art, the following practices can cultivate presence and openness:

Slow Looking

Spend extended time with an artwork. Notice:

- Color, texture, form

- Emotional and bodily responses

- Recurrent thoughts or memories

Journaling and Reflection

Write or sketch your responses. Questions to explore:

- What does this work evoke within me?

- Does it raise questions of meaning, existence, or value?

Meditation with Art

Use art as a meditation anchor:

- Focus on a detail

- Let your attention widen to include your breathing and bodily sensations

This approach reframes viewing as participation rather than observation.

Conclusion

The spiritual dimension of art transcends boundaries of culture, medium, and era. Whether in ancient cave paintings or contemporary installations, spiritual art invites us into deeper awareness—of ourselves, others, and the larger mysteries of existence. At its best, art becomes more than a visual expression; it becomes a bridge between the seen and unseen.